Betwixt Reason and Result

I’m writing to you from a cheap hostel in downtown Toronto (Hostelling International, highly recommend for solo travel, I have stayed in SF, LA, NY, PHL, TO, NZ and more I probably forget) where a cute anecdote just happened that illustrates an important principle.

This hostel has a dive bar in the basement. If you’re the social drinking type it’s pretty cool, except tonight they have a really bad band playing. Like some dude wailing away on the mic trying to be all metal, but halfheartedly. His band is doing something, but unfortunately his mic is tuned up so high you can’t hear them. It’s loud and it’s bad. This would be fine, except… in the study area where I am typing this, where all the young kids are busy working on their laptops and such… this hostel has also chosen to put the bar’s music on blast on the wall TV.

It’s my second evening here. It was the same deal last night too. Clearly nobody here is enjoying the “music”. They tolerate it. Most of us have headphones in. One girl even has her fingers in her ears as she reads a magazine. I tolerate it too, for hours.

Eventually I have enough, ask around if anyone minds, get a chair, stand on it to reach up to the TV, and turn it off.

Blissful silence.

Then: smiles, thumbs up, and one girl even says “oh thank god”. And we get back to our activities, this time sans faux-metal caterwauling.

Now: I don’t know if I was allowed to do that. The TV was hostel property. Someone clearly turned it on and left it on for a reason. But at the same time it was clear nobody actually in the study area was enjoying it, and I even asked before I did it. And after I did it, everybody was visibly happier. It took 30 seconds for the result of hours of slight improvement in quality of life.

Making the change you want to see in the world

This is a small, meaningless anecdote, and I’m not holding myself out to be some paragon of independent thought, but I find it a nice microcosm of many similar, far more high stakes situations in real life. Why didn’t anyone do what I did? Was it because there was no explicit permission? Was it that everyone at the hostel was transitory? Was it a normative issue; nobody else is doing anything about it, so I shouldn’t?

I think these are good academic questions, but the wrong ones as far as personal philosophy is concerned. It doesn’t matter what others thought. It matters that I was personally being inconvenienced by this thing, and that I could take a simple action to address it. So I did. The fact that it was a reversible action (a la Collison and Bezos) also made it easier to ask for forgiveness rather than permission.

I often say that I don’t take my own advice anywhere near as much as I should, and this is especially true here. I have had a lot of conditioning to accept things as they are and to work within the system. My life has definitely suffered because I failed to question defaults. Even among my peers I’m a relative deviant and outlier, but even I know that I don’t push the envelope anywhere close to what I have seen smarter and bolder friends do. To be clear, I’m not talking about doing anything immoral or illegal or just plain rude, I’m just saying we could all do a little better for ourselves and for our environment by exploring that vast gray area between the status quo and the clearly not allowed.

The Importance of Being Unreasonable

Everyone should know the George Bernard Shaw quote:

“The reasonable man adapts himself to the world: the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

A little gendered, but you get the drift. In fact my objection to it has more to do with the negative connotations of “unreasonable” - that you cannot be reasoned with, and generally that you can be an ass to someone calmly trying to tell you why you can’t do a thing. I am not OK with that.

Framing is important to me, so I looked around for a more positive framing for this idea. I like this phrasing by George Mack:

4/ High Agency is a sense that the story given to you by other people about what you can/cannot do is just that - a story. And that you have control over the story. A High Agency person looks to bend reality to their will. They either find a way, or they make a way.

5/ Low agency person acepts the story that is given to them. They never question it. They are passive. They outsource all of their decision making to other people.

Of course, this is a cartoonish dichotomy of people between “supermen” and “sheep”. But it can be a useful mental model (”all models are wrong, but some are useful”). I recommend George’s whole twitter thread for even more perspectives on agency. In particular, Paul Graham describes this quality as the difference between being Relentlessly Resourceful and “hapless”, which is a nicely positive framing of this.

Ultimately, though, I still come back to this idea of “unreasonable”, but from a more literal perspective. Here’s Steve Jobs and the Janitor story:

Steve used to give employees a little speech when they were promoted to Vice President at Apple… Lashinsky calls it the “Difference Between the Janitor and the Vice President.” Jobs tells the VP that if the garbage in his office is not being emptied regularly for some reason, he would ask the janitor what the problem is. The janitor could reasonably respond by saying, “Well, the lock on the door was changed, and I couldn’t get a key.” It’s an irritation for Jobs, but it’s an understandable excuse for why the janitor couldn’t do his job. As a janitor, he’s allowed to have excuses. “When you’re the janitor, reasons matter,” Jobs tells newly minted VPs, according to Lashinsky. “Somewhere between the janitor and the CEO, reasons stop mattering,” says Jobs, adding, that Rubicon is “crossed when you become a VP.”

To be “unreasonable” is to literally not have reasons factor in to your process for not getting things done. The buck stops with you, figure it out. This is the principal-agent problem: when you were merely an agent, as long as you “did your job”, you were fine. Ironically the process of becoming “high agency” makes you into more of a principal than an agent. You may find this comical but all good senior leadership lives on being able to delegate execution.

Bad leadership can be “unreasonable” too; an unprincipled “do whatever it takes” attitude often leads to strategy churn, cutting corners and sometimes even jail.

The vast gray area

Now, I instinctively dislike a pure results-driven approach: after all, shouldn’t we be focusing on Systems over Goals and obsess over process over outcomes? How to reconcile the desire to be “reasonable” vs ruthlessly getting results by any means necessary?

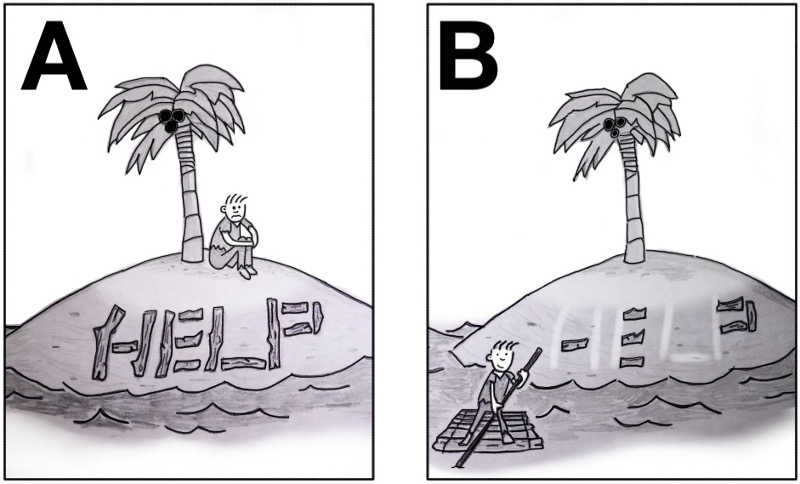

I will argue that “high agency” can occupy the liminal space between the two. Take another look at the graphic from George Mack’s tweet:

Was the person allowed to build that raft? Unclear, but probably yes. Would it help save his life? Unclear, but at least he has a shot. Would 99% of people have just sat around waiting for help to arrive or things to improve? Absolutely.

The status quo is usually overly conservative. It has the benefit of being tried and tested and allowed, but it is slow to adapt to changing rules, and frankly not enough alternatives are usually tested before everyone settled on this status quo. I liken this to the local vs global optima concept in Mathematics and Machine Learning: we know what we have right now works, but we don’t know if there’s something better unless we go look. Too few people do.

What prevents us from exploring the space of possibilities? There are many reasons, but I think our reasonableness is a big one. A reasonably smart person like you or I can reason our way out of doing anything. That’s good for academic and socratic debate, but bad for actually taking any action. And of course, there’s the trump card: “If something better could’ve been done, it would already have been done”. This is remarkably lazy thinking and characteristic of reasonable people.

The popular joke that comes to mind in this genre is the Economist refusing to believe there can be \$20 on the ground because if it did it would already have been picked up.. It enforces a false dichotomy that either the market is totally efficient and the $20 doesn’t exist, or the $20 exists and the market never efficient. But both can be true. Someone’s got to be first to pick up the \$20.

YOU can be that first person to do something. And you should.