Choice Architecture

How Companies Offer Choice to Reduce Choice

In their book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein coined the term Choice Architecture to describe how the way you present choices to consumers can heavily affect their decisionmaking. It’s been used for everything from encouraging people to save more for retirement or registering for organ donations, with dozens of governments setting up dedicated “Nudge Units”.

Thaler later won the Economics Nobel for his contributions to behavioral economics, but it occurred to me today that this pinnacle achievement of choice architecture must seem absolutely elementary to its master practitioners:

Gyms and Startups.

Selling like a Gym

I signed up for a gym recently and it was a surprisingly convoluted experience.

Go on to the Anytime Fitness website and try to figure out how much membership costs.

I’ll save you some time - you won’t find it. You need to schedule a free trial, go down, tour the facilities, work out, and then at the end, their “membership consultant” will sit you down at a nice table with a refreshing drink to tell you about their options. Reciprocity at its finest. But we’re not here to talk about Influence - let’s look at the choices offered:

This is how it works out:

- For the base membership price, a commitment of 6 months will cost you $128 per month (a 1 month commitment would be $148).

- On top of the base membership, there’s an “Admin” fee of $105, together with a “Key” fee of $75.

- During this special period, they are running a promotion - they will waive the Admin fee if you sign up for personal training, and you can book 5-30 sessions at the cost of $450-$2,100.

- However if you sign up RIGHT THIS SECOND you can get a special deal of 3 sessions of personal training at $160.50! What a deal!

Got all that? I went in wanting to sign up for a gym, I came out with a complex financial plan.

Ordinarily, you might consider the Admin fee of $105 exorbitant compared to the monthly membership of $128. But you are immediately bombarded with this special “promotion” that offers something of value for more money. Now, the $160.50 in personal training doesn’t look so bad! Among the barrage of dollars and choices, you hopefully have also forgotten that they’re also charging $75 to set up a keycard for you.

This is choice architecture.

Startups

Having been involved in a few job offer discussions at Silicon Valley companies now, I noticed they all use the same playbook:

- You start interviewing with them, with no idea what they pay

- After 1-2 months you finish the interview process, you’re tired (you’ve been interviewing with others too, as you should) and want it to be over, they tell you you are the best thing since sliced bread

- You’ve absorbed enough advice to know that you should never name the first number (more thoughts collected in my book)… and your recruiter knows that too

- So they happily name TWO numbers:

- Offer A with X cash and Y options

- Offer B with (X minus a bit) cash and (Y plus a bit) options

And now you have the power to choose your compensation according to how much you believe in the company! How generous, right?

This, too, is choice architecture.

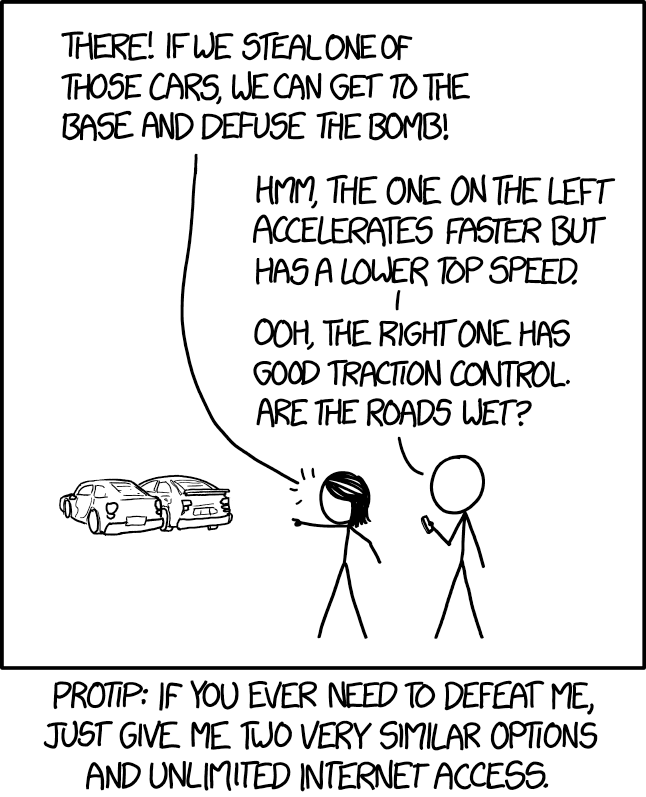

Relevant XKCD?

To be clear, I don’t mean that there’s anything malicious going on. It’s an extremely standard playbook at this point. I’ve taken this deal myself, twice. It’s just that giving you that choice focuses you on the options they give you, rather than all the other options available to you which could include higher total compensation. It also establishes an extremely tight “range” - a low end and a high end, and if the company is extra savvy, the tradeoff between cash and stock will be at a much higher valuation than their last investment. All fair game.

But you see how presenting this choice is better than presenting one offer without a choice? It hands limited “agency” back to the prospective hire, within predetermined bounds, and the hire will have to fight extra hard to justify something much higher (basically a higher offer from a close peer or that you are completely misleveled). After all, you gave them a choice in how much cash they want! By the way those options are simultaneously worth nothing and worth millions.

You have the choice to not accept these choices, and to propose different rules and different structures. Of course, the likelihood of acceptance decreases dramatically as you go outside the company playbook. I’m not smart enough to offer you a menu of what those other choices are - but some in-demand people like Daniel Vassallo are experimenting with 1/4 time employment. I’ve known others to work contract jobs for only half the year, and spend the other half surfing around the world. Or you could start an agency or company building the tool or service you would’ve been working on anyway, sell it in lieu of employment and maybe get acquihired. Lots of choices that are not Offer A nor Offer B.

Choice Architecture in the Wild

I want to reiterate that there’s nothing inherently malicious about Choice Architecture. Kasey Speakman raised a very great point that parents also do it for their children. It’s just that most of the time it’s done, it’s done with the benefit of the choice-giver in mind, rather than the choice-taker. It respects agency but puts down extremely tight boundaries around what you’re allowed to do. Most of the time that’s just how the game is played, and you can just go along with it. But every now and then it’ll be used for something truly exploitative and you’ll want to know how to spot it and reject it out of hand before being manipulated into a bad deal.

You often also see (un?)intentionally bad choice architecture in surveys and opinion polls - a leading question like Do you think buying the latest smartphone is a waste of money? may get a lot of yeses but fail to reflect actual behavior. This is why experienced data analysts always ask to see the original question alongside the interpreted survey results.

Two last examples I’ll leave you with so you can see this in the wild: indie book makers love choice architecture.

- Wes Bos is pretty open about how he does it. Check out Mastering Gatsby: as of time of writing and in my country, the Starter Course with 6 Modules costs $82, whereas the Master Package with 13 Modules costs $97. Who’s going to buy the Starter course?

- Adam Wathan likes the “shitty version/full version” model too - Refactoring UI charges $79 for just the book, and $149 for the book plus a bunch of extras. He also is very open that this pricing model is pretty much designed to set levels so that it appeals to people who would normally flinch at paying $79 for a PDF.

In pricing for my book, I used the Ryan Delk pricing formula from Joel Hooks. It hasn’t worked that well - I suspect mainly because I haven’t done a good enough job articulating the value in the 3 choices, which is more work compared to the 2 choice model. Still, nothing malicious meant. When you are putting infinitely replicable zero margin stuff up for sale, there is no marginal “cost of goods sold”, so it is “monkey see, monkey do” when it comes to giving Choices.