Networking Essentials: Content Distribution

This is the eighth in a series of class notes as I go through the free Udacity Computer Networking Basics course.

In HTTP, your browser makes a request to a server over a network, and receives a response with content. The request is layered over a byte stream protocol, usually TCP. The server doesn’t retain any information about the client, so it is “stateless” (there are common ways to get around this).

HTTP Requests

Note that this is true for HTTP/1; HTTP/2 is on the rise and is not covered here

The content of a HTTP Request includes

- Request line

- the method of a request: GET, HEAD, POST, PUT, DELETE

- the requested URL endpoint e.g. “/index.html”

- the HTTP version we are using e.g. 1.1

- Headers

- the referrer - what caused the page to be requested

- the User-Agent - the client software used eg Chrome or Firefox

HTTP Response

Note that this is true for HTTP/1; HTTP/2 is on the rise and is not covered here

The content of a HTTP Response includes

- Status line

- the HTTP version we are using e.g. 1.1

- the response code eg

100, 200 OK, 300, 301, 404, 500

- Other Headers

- Location (for redirecting)

- Server (for server software)

- Allow (for HTTP methods allowed)

- Content-Encoding (eg is it compressed)

- Content-Length (in bytes)

- Expires (for caching)

- Last-modified

HTTP/2

HTTP/2 doesn’t use newline separated requests and responses, and instead splits data into smaller messages and frames. It also allows new features like pseudo-header fields (:path, :authority, etc) and ALPN protocol identifiers. It is out of scope for this article but Google Web Fundamentals and HPBN have good resources alongside Wikipedia.

Caching

To improve web performance, we cache things so that we don’t have to make so many hops through to the origin server every time we need something we fetch very often. We can cache things in various places:

- in the browser (aka “locally”)

- in the network (your ISP, or CDNs)

Caching in the network (say by your ISP) can in particular benefit if multiple clients (aka users) all request the same thing, which makes loading faster and also saves money for the ISP because it doesnt have to route through other expensive links to reach the origin.

Caches periodically expire content based on the expire setter and check back with the origin. If nothing has been modified, the origin server sends back a 304 Not Modified response.

The decision of where to cache is done in two ways:

- Explicit browser configuration to point to a local cache

- Server directed - the origin server might point direct you to a cache. This is done with a special reply to a DNS request

(Web) CDNs

**What is A CDN?

- CDNs are an overlay network of web caches designed to deliver content to the client from the optimal (usually geographically closest) location.

- Distinct, geographically disparate servers close to users.

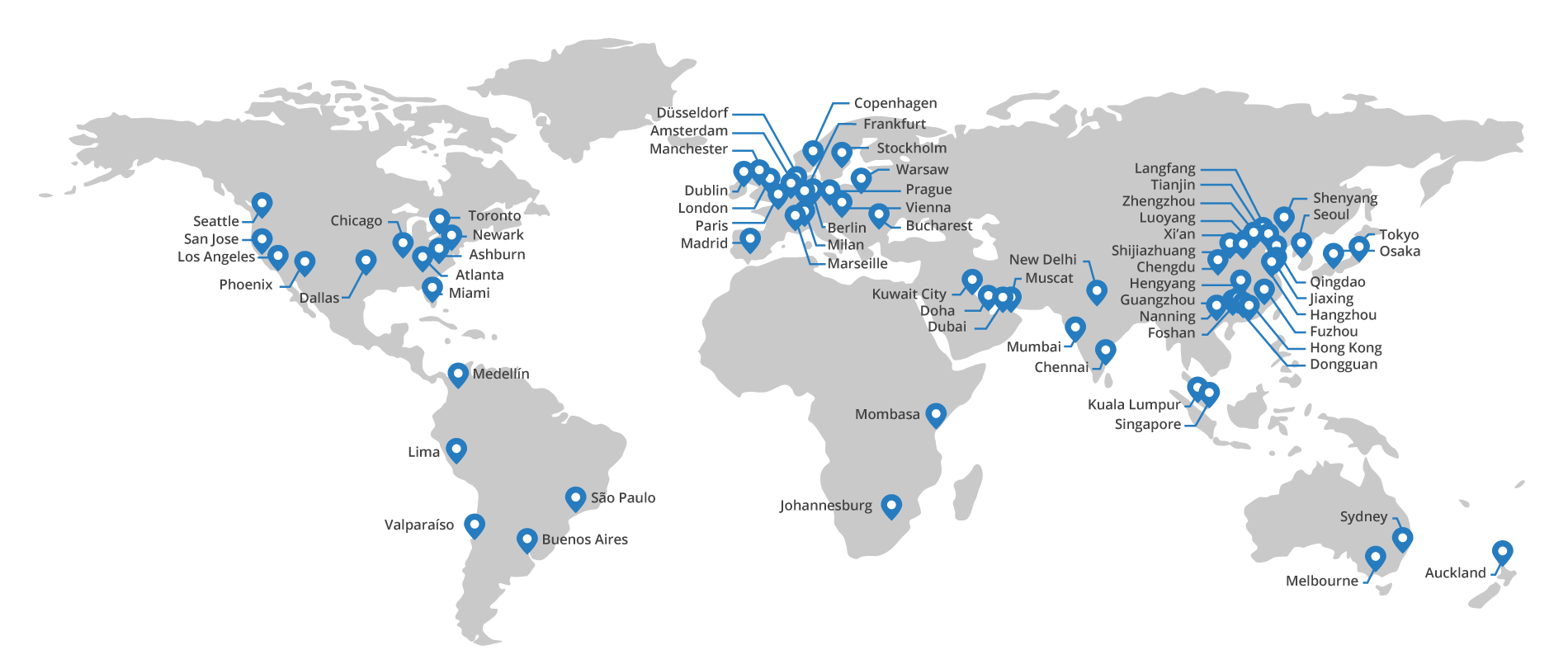

CDNs can be owned by large content providers like Google, or independent Networks (like Akamai and Netlify) and ISPs (like AT&T or Level 3). To give idea of the scale of these networks, Google has about 30,000 frontend cache nodes, while Akamai has 85,000 unique caching servers in 1000 unique networks around the world in 72 countries.

Challenges in running a CDN

The goal is to replicate content on many servers, but unaddressed are:

- How to replicate the content?

- Where to replicate it?

- How clients should find the replicated content?

- How clients should choose server replica? (aka the “server selection problem”)

- How to direct clients once the replica has been selected? (aka the “Content Routing” problem)

How server selection works in a CDN

Which server to direct client to?

- Lowest load?

- Lowest latency? <- this is often the winner, since latency is important to web performance

- any random “alive” server?

Content Routing aka How clients get redirected to a server

- Routing-based redirection (eg anycast). This is the simplest but it gives service providers very little control.

- Application-based routing (eg HTTP redirect). This is effective, but requires that the first request go to the origin server so it doesnt really help reduce first load latency

- Naming-based routing (eg DNS). This is the most common approach as the client looks up a domain name and the response is the address of a nearby cache. This provides significant flexibility in directing different clients to different server replicas. It is fast and provides fine-grained control.

Naming-based redirection

When you look up symantec.com from New York, you might get a CNAME (Canonical Name) directing you to a nameserver like a568.d.akamai.net. The A response from a568.d.akamai.net will then direct you to an IP address like 207.40.194.46.

When you do the same from a different city, the nameserver will respond with a different IP address like 81.23.243.152, which is closer to you in that city. This is how naming based redirection works.

CDN and ISP peering

CDNs and ISPs are very symbiotic. CDNs like ISPs because:

- CDNs peering with ISPs provides better throughput since there are no intermediate AS hops.

- Having more vectors to route content (redundancy) increases reliability

- Having direct connectivity to multiple networks where the content is hosted allows the ISP to spread the content across multiple transit links, which helps deal with bursty traffic, while reducing the 95th percentile load and thus its traffic costs.

ISPs like CDNs because:

- they improve performance for customers

- they lower transit costs

Bit Torrent

BitTorrent is a peer-to-peer CDN for file sharing and specifically large files.

Origin servers have problems with large files because everyone requesting from that file means congestion or overload for the origin server. So the solution is to chop up the file and replicate it at all peers, so you fetch the content from other peers instead of a single server.

The publishing process is:

- A peer creates a “torrent”, which has an assigned tracker and lists all the chunks of a file (along with their checksum)

- “Seeders” create the initial copy of the file

- To download, a client contacts the tracker which has a list of all the “seeders”. It also returns a random list of “leechers”, which are clients that contain incomplete copies of the file

- The client starts to download chunks of the file from the seeder

- These parts may be different from those downloaded by other clients.

- The clients can now begin to swap chunks with one another.

The problem with this model is freeloading, where a client leaves the network as soon as it finishes downloading a file, not providing a benefit to others who also want the file.

The solution to freeloading is choking - the temporary refusal to upload chunks to another peer that is requesting them. This seems a counterintuitive restriction, but combined with the rule that if a peer can’t download from a client then it won’t upload. This eliminates the incentives to freeload.

Chunk Swapping

The algorithm for swapping chunks is important for Bit Torrent. It uses a “rarest piece first” strategy, leaving the most common pieces to download at the end. However, by definition, rare pieces may be available at the fewest clients, so that may slow download times. Clients may opt to start off with “random piece first” strategy from seeders.

By the end, you just want to request missing pieces from all peers and cancel redundant requests when the piece arrives.

Distributed Hash Tables

DHT’s enable structured content overlay. A common type of DHT is Chord, which uses consistent hashing to establish an intuitive, scalable, distributed key-value “lookup service” (e.g. DNS or directories) with provable correctness and good performance.

Consistent Hashing

The main idea here is that Keys and Nodes map to the same ID Space.

A hash function like SHA1 is used to assign identifiers to both Keys (eg hashing the key) and Nodes (eg hashing the IP address). Once this is done we map the key IDs to the Node IDs so we know which is responsible for the lookups for a particular key. Chord’s idea is that a key is stored at its successor, aka the node with the next highest ID. (if the ID is at the highest number, it wraps around to the first node, hence the ring format)

This system offers load balancing because nodes receive roughly the same number of keys (given a uniformly distributed hash algorithm like SHA1).

This system also offers flexibility because when a node enters or leaves a network, only some keys need be remapped.

The final part of the system is that nodes need to be able to find other nodes. You could make every node know every other node, but that would require O(N) storage. You could make every node only know their success, which makes for O(N) lookup. The happy midddle is Finger Tables, where every node knows m other nodes, with exponentially increasing distance. For example, Node 10 will maintain address for:

- 10 + 2^0: Node 11

- 10 + 2^1: Node 12

- 10 + 2^2: Node 14

- etc

This reduces both storage and lookup to scale at O(log N).

Next in our series

Hopefully this has been a good high level overview of how CDNs, BitTorrent and Distributed Hash tables work. I am planning more primers and would love your feedback and questions on: